Brittania

All day long the packing up went on, and one by one the shows moved off, and the marketplace became more empty.

In the afternoon Toby came to the caravan to inform Rosalie that the Royal Show of Dwarfs was just going to start, and Mother Manikin wanted to say goodbye to her.

“Mind you thank her, Rosalie,” said the sick woman, “and give her my love.”

“Yes, Mummy dear,” said the child. “I won’t forget.”

She found the four little dwarfs sitting in a tiny covered waggon, in which they were to take their journey. Rosalie was cautiously admitted, and the door closed carefully after her. Mother Manikin took leave of her with tears in her eyes. They were not going to the same fair as Rosalie’s father, and she did not know when they would meet again. She gave Rosalie very particular directions about the beef-tea, and slipped in her pocket a tiny parcel, which she told her to give to her mother. And then she whispered in Rosalie’s ear, “I haven’t forgotten to ask the Good Shepherd to find me, child. And don’t you leave me out, my dear, when you say your prayers at night.”

“Come, Mother Manikin,” said Master Puck, “we must be off!”

Mother Manikin shook her fist at him, saying, “Old age must have its liberties, and young things should not be so impatient.”

Then she put her little arms round Rosalie’s neck and kissed and hugged her; and the three other dwarfs insisted on kissing her, too. And as soon as Rosalie had gone, the signal was given for their departure, and the Royal Show of Dwarfs left the marketplace.

Rosalie ran home to her mother and gave her Mother Manikin’s parcel. There were several paper wrappings, which the child took off one by one, and then came an envelope, inside which was some money. She took it out and held it up to her mother; it was twenty dollars!

Good little Mother Manikin! she had taken those twenty dollars from her small bag of savings, and she had put it in that envelope with even a gladder heart than Rosalie’s mother had when she received it.

“Oh, Rosalie,” said the sick woman, “I can have some more beef-tea now!”

“Yes,” said the child. “I’ll get the meat at once.”

And it was not only at her evening prayer that Rosalie mentioned Mother Manikin’s name that day; it was not only then that she knelt down to ask the Good Shepherd to seek and to save little Mother Manikin.

All day long Rosalie sat by her mother’s side, watching her tenderly and carefully, and trying to imitate Mother Manikin in the way she arranged her pillows and waited upon her. And when evening came, the large square was quite deserted, except by the cleaners, who were going from one end to another sweeping up the rubbish which had been left behind by the showmen.

Rosalie felt very lonely the next day. Toby had slept at an inn in the town, and was out all day at a village some miles off, to which his master had sent him to procure something he wanted at a sale there. The marketplace was quite empty, and no one came near the one solitary caravan—no one except an officer of the Board of Health, to inquire what was the cause of the delay, and whether the sick woman was suffering from any infectious disease. People passed down the marketplace and went to the various shops, but no one came near Rosalie and her mother.

The sick woman slept the greater part of the day, and spoke very little; but every now and then the child heard her repeat to herself the last verse of her little hymn—

“Lord, I come without delaying,

To Thine arms at once I flee,

Lest no more I hear Thee saying,

‘Come, come to Me.’ ”

And then night came, and Rosalie sat by her mother’s side, for she did not like to go to sleep lest she should awake and want something. And, oh, what a long night it seemed! The Town Hall clock struck the quarters, but that was the only sound that broke the stillness. Rosalie kept a light burning, and every now and then mended the little fire, that the beef-tea might be ready whenever her mother wanted it. And many times she gazed at her picture, and wished she were the little lamb safe in the Good Shepherd’s arms. For she felt weary and tired, and longed for rest.

The next morning the child heard Toby’s voice as soon as it was light.

“Miss Rosie,” he said, “can I come in for a minute?”

Rosalie opened the door, and Toby was much distressed to see how ill and tired she looked.

“You mustn’t make yourself ill, Miss Rosie, you really mustn’t!” he said reproachfully.

“I’ll try not, Toby,” said the child. “Perhaps the country air will do me good.”

“Yes, missie, maybe it will. I think we’d better start a day early, because I don’t want to go fast; the slower we go the better it will be for Missis. And we will stop somewhere for the night; if we come to a village, we can stop there, and I’ll get a hole in some barn to creep into, or if there’s no village convenient, there’s sure to be a haystack. I’ve slept on a haystack before this, Miss Rosie.”

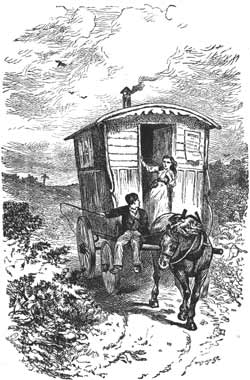

In about half an hour Toby had made all ready, and they left the marketplace. Very slowly and carefully he drove, yet the shaking tried Rosalie’s mother much. Her cough was exceedingly troublesome, and her breathing was very bad. She was obliged to be propped up with pillows, and even then she could hardly breathe. The child opened the caravan door, and every now and then spoke to Toby, who was sitting just outside. He did not whistle today, nor call out to his horse, but seemed very thoughtful and quiet.

Towards evening Rosalie’s mother fell asleep—such a sweet, peaceful sleep it was, that the child could but wish it to continue. It made her so glad to hear the coughing cease and the breathing become more regular, and she dreaded lest any jolting of the cart should awake her and make her start up again.

“What do you think of stopping here for the night, Miss Rosie?” said Toby.

They had come to a very quiet and solitary place on the borders of a large moor. A great pine forest stretched on one side of them, and the trees looked dark and solemn in the fading light. At the edge of this wood was a stone wall, against which Toby drew up the caravan, that it might be sheltered from the wind.

On the other side of the road was the moor, stretching on for miles and miles. And on this moor, in a little sheltered corner surrounded by gorse bushes, Toby had determined to sleep.

“I shall be close by, Miss Rosie,” he said. “I sleep pretty sound, but if only you call out ‘Toby,’ I shall be at your side in a twinkling; I always wake in a trice when I hear my name called. You won’t be frightened, Miss Rosie, will you?”

“No,” said Rosalie. “I think not.”

But she gazed rather fearfully down the road at the corner of which they had drawn up. The trees were throwing dark shadows across the path, and their branches were waving gloomily in the evening breeze. Rosalie shivered a little as she looked at them and at the dark pine forest behind her.

“I’ll tell you what, Miss Rosie,” said Toby, as he finished eating his supper, “I’ll sit on the steps of the caravan, if you are frightened at all. No, no, never you mind me; I shall be all right. One night’s sitting up won’t hurt me.”

But Rosalie would not allow it; she insisted on Toby’s going to sleep on the heather, and made him take her mother’s warm shawl, that he might wrap himself in it, for it was a very cold night. Then she carefully bolted the caravan door, closed the windows, and crept to her sleeping mother’s side. She sat on the bed, put her head on the pillow, and tried to sleep also. But the intense stillness was oppressive, and made her head ache, for she kept sitting up in the bed to listen, and to strain her ears—longing for any sound to break the silence.

Yet when a sound did come—when the wind swept over the fir trees, and made the branches which hung over the caravan creak and sway to and fro—Rosalie trembled with fear. Poor child! the want of sleep the last few nights was wearing on her, and had made her nervous and sensitive. At last she found the matches and lighted a candle, that she might not feel quite so lonely.

Then she took her Testament from the box and began to read. As she read, little Rosalie felt no longer alone. She had a strange realisation of the Good Shepherd’s presence, and a wonderful feeling that her prayer was heard, and that He was indeed carrying her in His bosom.

If it had not been for this, she would have screamed with horror when, about an hour afterwards, there came a tap at the caravan door. Rosalie jumped from her seat, and peeped out between the muslin curtains. She could just see a dark figure crouching on the caravan steps.

“Is it you, Toby?” she said, opening the window cautiously.

“No, it’s me,” said a girl’s voice. “Have you got a fire in there?”

“Who are you?” said Rosalie fearfully.

“I’ll tell you when I get in,” said the girl. “Let me come and warm myself by your fire!”

Rosalie did not know what to do. She did not much like opening the door, for how could she tell who this stranger might be? She had almost determined to call Toby, when the sound of sobbing made her change her mind.

“What’s the matter?” she said, addressing the girl.

“I’m cold and hungry and miserable!” she said with a sob. “And I saw your light, and I thought you would let me in.”

Rosalie hesitated no longer. She unbolted the door, and the dark figure on the steps came in. She threw off a long cloak with which she was covered, and Rosalie could see that she was quite a young girl, about seventeen years old, and that she had been crying until her eyes were swollen and red. She was as cold as ice; there seemed to be no feeling in her hands, and her teeth chattered as she sat down on the bench by the side of the stove.

Rosalie put some cold tea into a little pan and made it hot. And when the girl had drunk this, she seemed better, and more inclined to talk.

“Is that your mother?” she said, glancing at the bed where Rosalie’s mother was still sleeping peacefully.

“Yes,” said Rosalie in a whisper. “We mustn’t wake her, she is very, very ill. That’s why we didn’t start with the rest of the company. And the doctor has given her some medicine to make her sleep while we’re traveling.”

“I have a mother,” said the girl.

“Have you?” said Rosalie. “Where is she?”

But the girl did not answer this question. She buried her face in her hands and began to cry again.

Rosalie looked at her very sorrowfully. “I wish you would tell me what’s the matter,” she said, “and who you are.”

“I’m Britannia,” said the girl, without looking up.

“Britannia!” repeated Rosalie, in a puzzled voice. “What do you mean?”

“You were at Lesborough, weren’t you?” said the girl.

“Yes; we’ve just come from Lesborough.”

“Then didn’t you see the circus there?”

“Oh, yes,” said Rosalie; “the procession passed us on the road as we were going into the town.”

“Well, I’m Britannia,” said the girl. “Didn’t you see me on the top of the last car? I had a white dress on and a scarlet scarf.”

“Yes,” said Rosalie, “I remember; and a great fork in your hand.”

“Yes; they called it a trident, and they called me Britannia.”

“But what are you doing here?” asked the child.

“I’ve run away; I couldn’t stand it any longer. I’m going home.”

“Where is your home?” said Rosalie.

“Oh, a long way off,” she said. “I don’t suppose I shall ever get there. I haven’t a penny in my pocket, and I’m tired out already. I’ve been walking night and day.”

Then she began to cry again, and sobbed so loudly that Rosalie was afraid she would awake and alarm her mother.

“Oh, Britannia,” she said, “don’t cry! Tell me what’s the matter?”

“Call me by my own name,” said the girl, with another sob. “I’m not Britannia now, I’m Jessie. ‘Little Jess,’ my mother always calls me.”

And at the mention of her mother she cried again as if her heart would break.

“Jessie,” said Rosalie, laying her hand on her arm, “won’t you tell me about it?”

The girl stopped crying, and as soon as she was calmer, she told Rosalie her story.

“I’ve got such a good mother; it’s that which made me cry,” she said.

“Your mother isn’t in the circus, then, is she?” said Rosalie.

“Oh, no,” said the girl; and she almost smiled through her tears—such a sad, sorrowful attempt at a smile it was. “You don’t know my mother or you wouldn’t ask that! No; she lives in a village a long way from here. I’m going to her; at least I think I am; I don’t know if I dare.”

“Why not?” said Rosalie. “Are you frightened of your mother?”

“No, I’m not frightened of her,” said the girl. “But I’ve been so bad to her, I’m almost ashamed to go back. She doesn’t know where I am now. I expect she has had no sleep since I ran away.”

“When did you run away?” asked the child.

“It was three weeks ago now,” said Jessie mournfully, “but it seems more like three months. I never was so wretched in all my life before; I’ve cried myself to sleep every night.”

“Whatever made you leave your mother?” said Rosalie.

“It was that circus; it came to the next town to where we lived. All the girls in the village were going to it, and I wanted to go with them, and my mother wouldn’t let me.”

“Why not?”

“She said I should get no good there—that there were a great many bad people went to such places, and I was better away.”

“Then how did you see it?” said Rosalie.

“I didn’t see it that day. And at night the girls came home, and told me all about it, and what a fine procession it was, and how the ladies were dressed in silver and gold, and the gentlemen in shining armor. And then I almost cried with disappointment because I had not seen it too. The girls said it would be in the town one more day, and then it was going away. And when I got into bed that night, I made up my mind that I would go and have a look at it the next day.”

“But did your mother let you?” said Rosalie.

“No; I knew it was no use asking her. I meant to slip out of the house before she knew anything about it; but it so happened that that day she was called away to the next village to see my aunt, who was ill.”

“And did you go when she was out?”

“Yes, I did,” said Jessie; “and I told her a lie about it.”

This was said with a great sob, and the poor girl’s tears began to flow again.

“What did you say?” asked little Rosalie.

“She said to me before she went, ‘Little Jess, you’ll take care of Maggie and baby, won’t you, dear? You’ll not let any harm come to them?’ And I said, ‘No, mother, I won’t.’ But as I said it my cheeks turned hot, and I felt as if my mother must see how they were burning. But she did not seem to notice it. She turned back and kissed me, and kissed little Maggie and the baby, and then she went to my aunt’s. I watched her out of sight, and then I put on my best clothes and set off for the town.”

“And what did you do with Maggie and baby?” said Rosalie; “did you take them with you?”

“No; that’s the worst of it,” said the girl. “I left them. I put the baby in its crib upstairs, and I told Maggie to look after it, and then I put the table in front of the fire, and locked them in, and put the key in the window. I thought I should only be away a short time.”

“How long were you?”

“When I got to the town the procession was just passing, and I stopped to look at it. And when I saw the men and women sitting upon the cars, I thought they were kings and queens. Well, I went to the circus and saw all that there was to be seen. Then I looked at the church clock, and found it was five o’clock, for the exhibition had not been till the afternoon. I knew my mother would be home, and I did not like to go back. I wondered what she would say to me about leaving the children. So I walked around the circus for some time, looking at the gilded cars, which were drawn up in the field. And as I was looking at them, an old man came up to me and began talking to me. He asked me what I thought of the circus; and I told him I thought it splendid. Then he asked me what I liked best, and I said those ladies in gold and silver who were sitting on the gilt cars.

“ ‘Would you like to be dressed like that?’ he said.

“ ‘Yes, that I should,’ I said, as I looked down at my dress—my best Sunday dress, which I had once thought so smart.

“ ‘Well,’ he said mysteriously, ‘I don’t know, but perhaps I may get you that chance; just wait here a minute, and I’ll see.’

“I stood there trembling, hardly knowing what to wish. At last he came back, and told me to follow him. He took me into a room, and there I found a very grand lady—at least she looked like one then. She asked me if I would like to come and be Britannia in the circus and ride on the gilt car.”

“And what did you say?” asked Rosalie.

“I thought it was a great chance for me, and I told her I would stay. I was so excited about it that I hardly knew where I was; it seemed just as if someone was asking me to be a queen. And it was not till I got into bed that I let myself think of my mother.”

“Did you think of her then?” said Rosalie.

“Yes; I couldn’t help thinking of her then. But there were six or seven other girls in the room, and I was afraid of them hearing me cry, so I hid my face under the covers. The next day we moved from that town; and I felt very miserable all the time we were traveling. Then the circus was set up again, and we went in the procession.”

“Did you like that?” asked the child.

“No; it was not as nice as I expected. It was a cold day, and the white dress was very thin, and oh, I was so dizzy on that car! It was such a height up; and I felt every moment as if I should fall. And then they were so unkind to me. I was very miserable because I kept thinking of my mother. And when they were talking and laughing I used to cry, and they didn’t like that. They said I was very different to the last girl they had. She had left them to be married, and they were looking out for a fresh girl when they met with me. They thought I had a pretty face, and would do very well. But they were angry with me for looking so miserable, and found more and more fault with me. They were always quarrelling; long after we went to bed they were shouting at each other. Oh, I got so tired of it! I did wish I had never left home. And then we came to Lesborough, and at last I could bear it no longer. I kept dreaming about my mother, and when I woke in the night I thought I heard my mother’s voice. At last I determined to run away. I knew they would be very angry. But no money could make me put up with that sort of life; I was thoroughly sick of it. I felt ill and weary, and longed for my mother. And now I’m going home. I ran away the night they left Lesborough. I got out of the caravan when they were all asleep. I’ve been walking ever since. I brought a little food with me, but it’s all gone now, and how I shall get home I don’t know.”

“Poor Jessie!” said little Rosalie.

“I don’t know what my mother will say when I get there. I know she won’t scold me—I shouldn’t mind that half so much—but I can’t bear to see my mother cry.”

“She will be glad to get you back,” said Rosalie. “I don’t know what my mummy would do if I ran away.”

“Oh, dear!” said Jessie. “I hope nothing came to those children. I do hope they got no harm when I was out! I’ve thought about that so often.”

Then the poor girl seemed very tired, and, leaning against the wall she fell asleep, while Rosalie rested once more against her mother’s pillow. And again there was no sound to be heard but the wind sweeping among the dark fir trees. Rosalie was glad to have Jessie there; it did not seem quite so solitary.

And at last rest was given to the tired little woman; her eyes closed, and she forgot her troubles in a sweet, refreshing sleep.