Immigrants

“He fainted, and wished in himself to die, and said, It is better for me to die than to live.” (Jonah 4:8)

The nickname “Greasy” was given to Paul when he was but eight years old under special circumstances that will be mentioned later. His real family name was Tikhomirov.1 He was the son of a farmer from one of the poorest villages in the Government of Mogilev. The family consisted of the father, the mother, and two children—ten-year-old Shura (Alexandra) and eight-year-old Pasha (Paul). They lived peacefully, were religious in the orthodox way, and enjoyed the respect not only of the inhabitants of their own village, but of those of all the district.

[1]:

[Refer to Glossary for pronunciations and definitions of italicized words.]

On the holy days, the local orthodox priest used to visit them to play cards with the father—not for money, but merely to pass the time. Sometimes the game was “Duratchki” (tomfool), in which it was customary for the losing one to suffer the pack of cards to be thrown at his nose. If either of the players had some money, they sent the children for liquor, which would put them in a hilarious mood. The priest, whom they called “Batushka” (Daddy), used to say, “It is no sin to drink with moderation. Even the Lord Jesus loved to be joyful, and at the wedding in Cana changed water into wine.”

The children loved to look on, and noted with special interest how the nose of the priest would become more and more red—they did not know whether it was from drinking the liquor or from the frequent hits with the pack of cards thrown at him cleverly by their father, who usually won the game. The good-natured priest used to say with a croaking voice, “He who will endure to the end will be saved. I shall have my turn, my beloved, and then look out, because it is written, ‘Owe no man any thing,’ (Romans 13:8) and, ‘With what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again.’ (Matthew 7:2; Mark 4:24)”

This hilarious life came to an abrupt end. Several successive bad harvests compelled the farmers of the village of Sosnovka to consider moving to Siberia. In groups they talked over the matter with one another and finally decided to send out messengers to find an appropriate piece of land in one of the Siberian districts. Because he was a clever and experienced man, Tikhomirov was among those landseekers. After three months the messengers returned; they had found land in the Government of Tomsk. Promptly selling their land and property, the farmers started on their way. This was in the year 1897.

During the trip, the trains made slow headway and had to make long stopovers at the crossroads in Samara, Chelyabinsk, and Omsk. The moving farmers had to wait for weeks to get trains for further travel. Their days and nights were spent in the small railroad stations, sleeping on the floor. The boiled water was not sufficient for all, nor could the people afford to buy warm food from the restaurants. Consequently, the poor, simple people satisfied themselves with dried herring or other dried fish and drank unboiled water. As a result, many had stomach trouble, and cholera set in. The older people were especially afflicted by the plague.

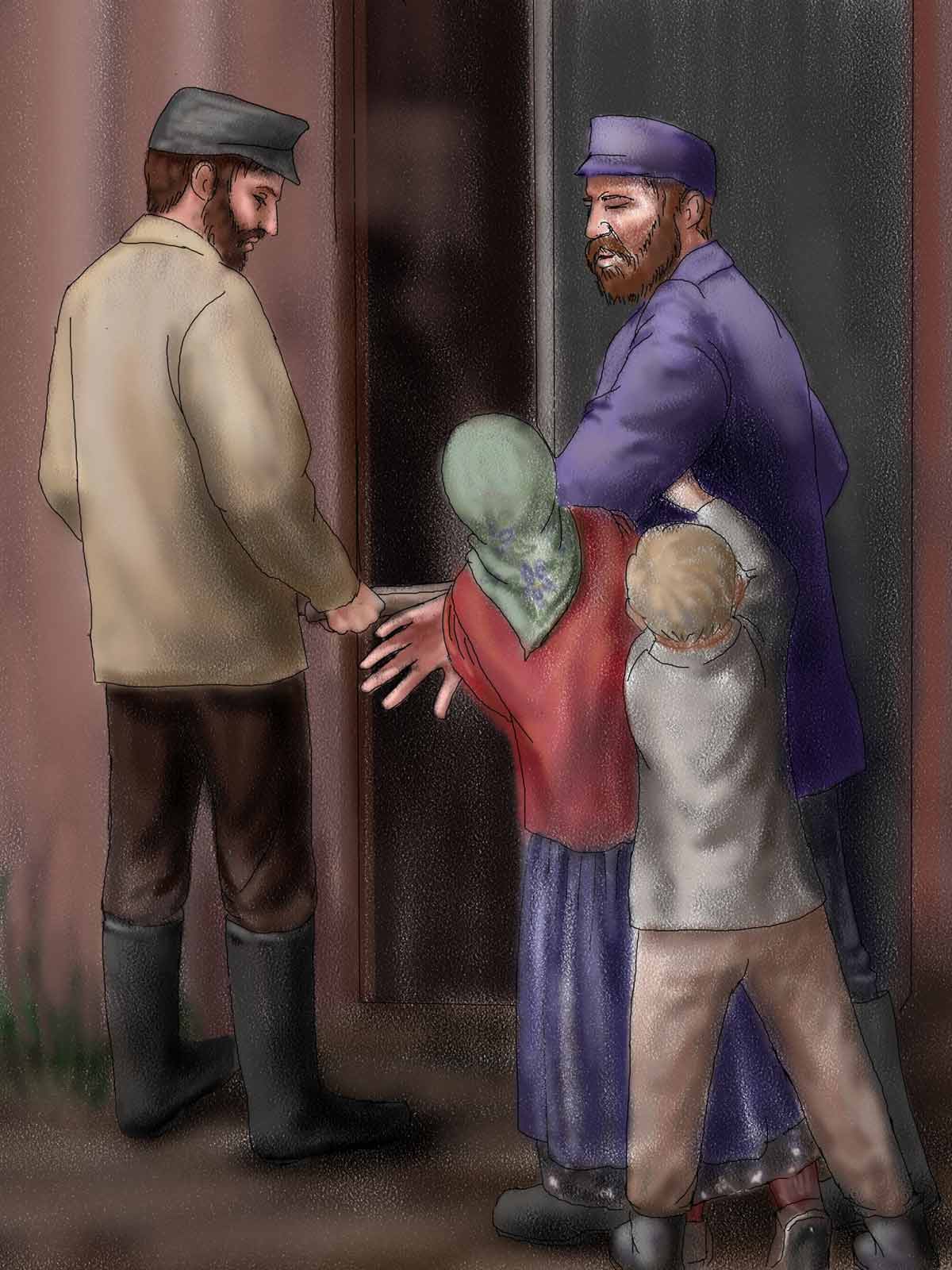

On the last stretch before reaching Tomsk, Mr. Tikhomirov became sick. All indications signified cholera. To the horror of his wife and children, at one of the stations he was taken from the train and put in the barracks for people with infectious diseases. It was only natural that Mrs. Tikhomirov and the children leave the train also. They found refuge not far from the barracks behind the snow fences along the railroad tracks. Daily they inquired about the condition of the father, but the report was worse every time.

After three days had passed, the sorrow-stricken mother had to tell the children that she also was sick. It was a heart-breaking scene when the mother was taken away on a stretcher from the crying children. In her they lost their last support. With a sad heart the mother parted from her children, suspecting that she would never see them again. But more terrible to her was the possibility that her beloved children soon would be orphans in a strange land.

As the mother was carried into the barracks, the desperate children ran crying behind the carriers until the heavy barracks door was slammed in their faces. How lonesome and miserable Shura and Pasha felt. As if bereft of their senses, they circled the barracks, calling now for their father and then for their mother. The only answer they received was a coarse cry from the guard, threatening them with a whipping if they would not leave the barracks. But the children did not cease crying and asking to be let in. They wanted to die with their parents, since they felt that they could not live without them. Thus they kept running around the barracks until late at night when the severe cold compelled them to think of their warmer clothing, which they had left with some other things behind the snow fences. However, when they came back to the spot where they had been camping, they found no sign of their baggage. Apparently someone had taken the few poor things of the immigrants.

Crawling behind the snow fences, the two children huddled together to keep warm. Shura was very concerned about her younger brother. During the night, which seemed to her like an eternity, she did not close her eyes. As soon as Pasha awoke the next day, the children hurried back to the barracks. The first guard they met told them, “Do not come again. This morning we carried away the body of your father, and your mother is likely to die today.”

But it was impossible to compel the children to leave the barracks. Again and again they looked through the windows and called for their mother. Would her beloved voice be silenced forever? Would she be only a cold corpse in the morning? Yes, that evening they were told that their mother had died an hour ago. Hugging each other, they sat behind the snow fences and cried bitterly.

That night even Pasha did not sleep; with his back against the snow fence he looked into the distance, where the rails seemed to disappear out of sight. In his childish mind the terrible happenings of the last few days passed again before him. When he finally saw a train approaching, he said, “Shura, I will live no longer without Father and Mother. Come, let us lay ourselves on the rails. The engine will crush us, and then we shall be dead. What do we have to live for now? Where shall we go, and to whom shall we be of any use?” With these words Pasha took his sister by the hand and dragged her to the rails.

Shura was terrified. She clasped her small brother in her arms and cried with sobs, “No!—for nothing in the world will I go with you to cast myself under the train. Neither will I let you go. I am terrified! It is terrible!”

“Let me go; I shall go alone!” cried the boy.

While they argued, the train rushed by. Pasha threw himself on his face to the ground and began to complain loudly, “Why have you held me back? I do not want to live anymore.” His sister spoke to him kindly in order to persuade him to give up his horrible thoughts. After a long time, when he had become calmer, he promised not to think anymore about death and not to leave her alone in the world.

After this the children huddled together in their refuge, waiting for the break of day, determined to see the grave of their parents in the morning. To the freezing and hungry children, the cold night seemed infinitely long. Finally, at daybreak they hastened to the cemetery, where, in an especially enclosed corner, those who had died of infectious diseases were buried. At the gate the children begged the keeper to let them in and show them the grave of their parents. But the man answered harshly, “How many bodies were carried out here only last night? How could I know who is buried here? Besides, ten bodies are usually thrown into one hole; sometimes even twenty.”

Not achieving anything, the children looked with eyes red from weeping through the cracks of the fence toward the irregular mounds of wet clay. For a long time they stood there crying and looking at the graves, until the keeper drove them away. Oppressed with sorrow, the two children returned to the snow fences—the silent witnesses of their cruel experiences of the last five days, including the parting from their beloved mother. This place had become the orphaned children’s home. Under the protection of these fences they began to consider what to do next.

The very thought of being put into the barracks for orphans seemed terrible to them; yet they realized that it would save them from starvation. Hunger was becoming more and more intense. Their meager supply of food, as well as their money, had been stolen along with the rest of their baggage.

Fear overshadowed the lonesome, hungry, freezing children, even though high above them the larks were joyfully singing their spring songs and the clear rays of the sun gilded everything around. In the hearts of the orphans it was a dark night. Their mutual sorrow drew the brother and sister together. Shura tried to be a mother to her little brother. She kissed him and tried to comfort him, saying, “We shall not despair, my beloved; God will not forsake us.”

The children decided to follow the railroad to the next village to beg a bite of bread, but just then they heard above them a coarse voice. “What are you doing here? To whom do you belong?” An unknown uniformed man appeared before them and looked at them searchingly. They became so completely confused that they could not say at once that they were the children of immigrants and had just recently lost their parents. The stranger commanded them to follow him and led them into the distribution office. There it was promptly decided to send them to the barracks for orphans, where they did not want to go, because it meant separation for them. The girls’ barracks were several railroad stations away. Not heeding the pleadings and tears of the children, the officials took Pasha to the boys’ barracks about two miles distant, while Shura was sent on the train to the girls’ home. The sorrow of the children at parting cannot be described, for they lost in each other all that was still dear to them on earth.